This is a continuation of what I have learned about acorn preparation.

Also see part 1, part 2, and part 3.

|

| Pomo boiling basket, stones, and tools |

Acorn

(Quercus sp.)

Part 4: Cooking

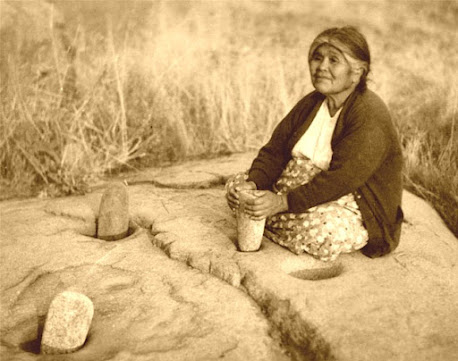

The Yosemite Miwok/Paiute

Indians cooked the one layer into a mush called nuppa. When working with the

fine layer, they made akiva (soup),

and with the coarse layer, they made nuppa

or water biscuits, uhlley. The traditional cooking method involved

baskets and hot stones. The thick layer

of acorn that sometimes stuck to the stones when they were removed from the

cooking basket made a special treat for the children, called acorn chips. These were made when the acorn had cooled and

hardened, and was then peeled off the stones. (Ortiz,

116-117)

The baskets were soaked

for several hours, then sealed even further by rubbing some of the flour on the

basket’s inside surface. Then the rest

of the flour and water was added. “The

volume of water varies according to the age of the acorns. Acorns stored for ten years don’t thicken as

readily as younger acorns, so less water is used. Less water is also used with ‘green’ acorn,

which thickens readily.” (Ortiz, 110)

The cooking stones, often

made of basalt or soapstone, were heated in a fire, often taking 30 minutes or

longer to become red-hot. One at a time,

they were lifted from the fire with sticks and quickly dipped into water twice

to remove ash from their surface. Then

they were gently placed in the cooking basket and rolled around. “Within minutes, the mush begins to bubble,

boil, blurp, and steam, filling the air with a nutty scent. Finally, four to six or more rocks later, the

meal is completely cooked to the desired soup or mush consistency.”

(Ortiz,

114)

The Eastern Mono, Southern Diegueño,

Luiseño, and Kamia boiled their acorn in ceramic pots. The Gabrielino used steatite vessels. But the use of baskets and stones was a

customary practice in the central and northwestern regions.

(Heizer

and Whipple, 304)

When

it is fully cooked, acorn has a subtle, delicate, nutty flavor. It is rarely seasoned, except by the use of

one last cooking stone, which is removed from the fire, rinsed, then lowered to

the surface of the acorn and moved over the top of the food to “scorch” it.

(Ortiz,

116)

The Paiute sometimes seasoned their acorn by pounding it with

clean incense cedar leaves. (Ortiz, 116) The Yurok slightly parched their acorns

before pounding; the Shasta roasted the moistened meal; the Pomo, Lake Miwok,

and Central Wintun mixed red earth with the meal; and the Plains and Northern

Miwok sometimes mixed ashes of Quercus

douglasii bark with it. (Heizer and Whipple, 304)

Cooked acorn jells

readily in cold water, which is a test for beginners to learn when to stop

cooking it. The uhlley water biscuits utilized this property: once the nuppa

was cooked, it was dropped into a tub of cold water from a wet bowl, forming a

“pretty shell-like shape, somewhat curved in on itself.”

(Ortiz,

117) The tub also contained

incense cedar branches, the oils from which gave the uhlley a “refreshing, foresty taste.” (Ortiz,

118)

Another way the acorn was

prepared was to form acorn cakes, small round patties which were placed on a

hot stone to cook. The flat stone had

previously had a fire built on it, which was removed when the stone was hot, and

the surface was swept clean. (Ortiz, 116) The Ohlone made this, too, by “boiling the

mush longer and then placed the batter into an earthen oven or on top of a hot

slab of rock.” Acorn bread was described

as “deliciously rich and oily” by early explorers. (Margolin, 44)

Also,

some Western Mono women cooked the flour and allowed it to congeal overnight

before serving. (Ortiz,

116)

Whether served as a thin soup, a thick mush, or a biscuit,

cake, or bread, acorn was utilized as a primary staple by California Indians

because it was highly nutritious as compared to wheat or maize (Heizer and Whipple,

305),

did not require farming practices like tilling or irrigation (Margolin,

44),

and was extremely plentiful throughout most of the state. In fact, “while the preparation of acorn

flour might have been a lengthy and tedious process, the total labor involved

was probably much less than for a cereal crop.”

(Margolin,

44)

|

| Looped stirrers used for handling hot cooking stones |

Here is a good introductory teaching packet regarding Native American food.

___________________________

I am trying to acquire freshly gathered acorns. If successful, I will try my hand at processing and cooking them,