This is a continuation of what I have learned about acorn preparation. See part one for more details on the references.

|

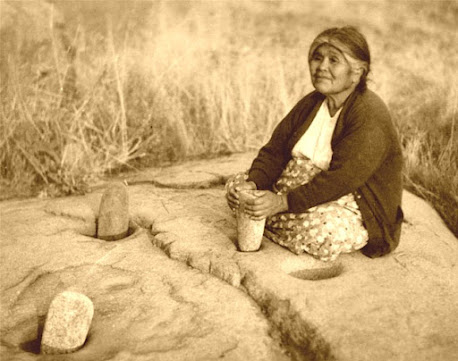

| Image credit: Bella Vista Ranch, "Bedrock Mortars for Grinding Acorns" |

Acorn (Quercus sp.)

Part 2: Preparation - Pounding

To be used, the acorn

must be cracked and shelled. Much of the

description that follows is how the Yosemite Miwok/Paiute Indians prepared

acorn, as found in Beverly Ortiz’s detailed book, It Will Live Forever.

One by one, each

acorn is held between the thumb and the index finger with its pointy end stabilized

against a flat, rough stone. The stone

provides a firm foundation for cracking, while its rough surface provides a

place to secure the pointed end.

The flat end of

the acorn, which was once attached to the oak tree, is then struck with the end

of a small, elongated rock (hammerstone) to crack its shell.

(Ortiz,

49)

The acorn was cracked by tapping it gently two or three times,

using a light, downward pressure. When

the shell split, a quiet popping sound was heard. The shell was removed and the kernel was

inspected for mold, mildew, or insect damage.

If any was found, the kernel was “returned to the earth” if extensive,

or cut away if minimal. Small black

spots, possibly from incomplete drying, were accepted, but completely black

kernels were not. (Ortiz, 49-51)

The kernels have a skin that is rust-colored and bitter, and

must be removed completely. Some oak

species have acorns with several grooves in the kernel, making it harder to

remove the skin. These grooves were

opened with a knife. Often the kernels

were rubbed together by hand and rolled against the basket to help loosen the

skins. Then they were tossed into the

air from a basket to allow the skins to blow away on the breeze. Any kernels with stubborn skins were put back out

to dry and then winnowed again.

(Ortiz,

53-58)

The pounding process had

specific techniques. Some people used hoppers,

bottomless baskets that were glued to a rock mortar to help contain the acorns

as they were crushed. Others pounded in shallow

depressions in the rock, piling up the powdered acorn as a cushion between the

pounding stone and the mortar. The rocks

used to crush the acorn were either “one-handed” or “two-handed”, depending on

their length (6 to 12 inches) and weight (four to fourteen pounds).

(Ortiz,

66-68)

Beginners need

about six handfuls of whole, freshly winnowed nuts to start. A palm-sized, one-hand pestle is balanced

upright in the mortar depression (even a slight, natural depression on a

bedrock will do) so it stands by itself, then one handful of nuts placed around

it. Grasped by the right hand, the pestle

is lifted, causing the nuts to fall into the depression. They’re now in place to be crushed with

several light, downward blows of the pestle.

These light blows

are designed to prevent the nuts from bouncing around the mortar. Once mashed, another handful of nuts is added

and gently crushed using the same technique, although this time the pestle is

balanced inside a small, bowl-shaped pile of crushed nutmeats. The process is repeated until four handfuls

of winnowed nuts are well crushed. (Ortiz, 68-69)

Once a quantity of acorn meal had been produced, it was used as

a cushion between the mortar and pestle, keeping the rocks from striking each

other and producing unwanted grit.

Adding more nutmeats to that pile gave several benefits: one is that the meal kept the nuts from

bouncing around while being pounded; the other is that the nuts kept the

natural oil in the meal from making it pasty.

“Whole kernels absorb the oil, preventing stickiness. … If it is too sticky, the acorn flour will

form little, beaded clumps during sifting, and it will not dissolve in water at

leaching time.” (Ortiz,

69-70)

This process was repeated

until the amount of acorn meal desired was created. The next step was sifting the meal to insure

its evenness. “You don’t want to have coarse and fine. You want to have fine flour. That’s the right way to make it. … So fine it blows away with the wind.” (Ortiz, 85) The coarse flour was

either returned for more pounding or kept as a starter for the next day’s

pounding.

(Ortiz, 92-93)